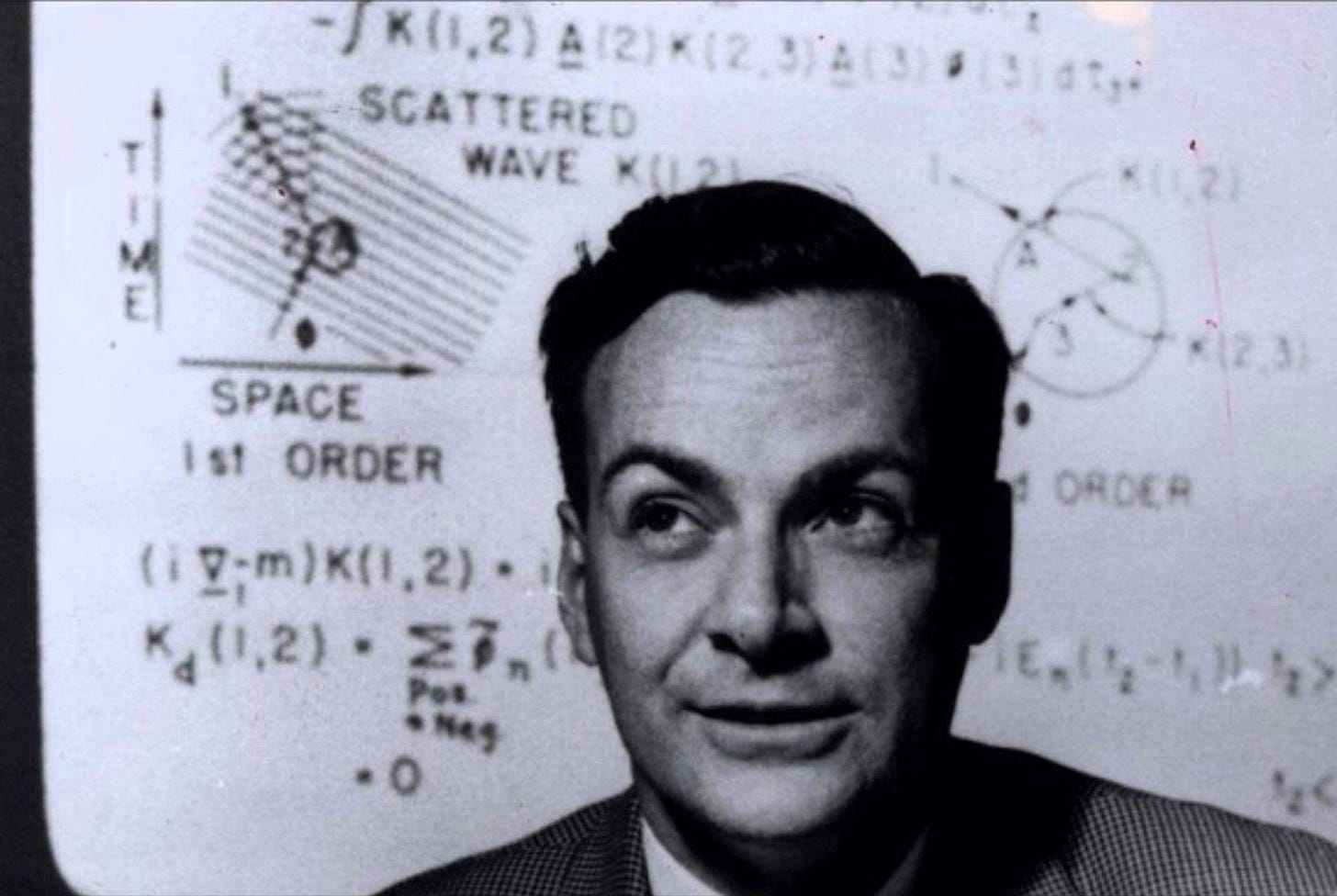

Building a Genius: The Trainable Mind of Richard Feynman

Genius isn’t innate; it’s built. Feynman showed that with curiosity, independence, and practical engagement, anyone can train their mind to think like a genius.

When we think of geniuses, we often imagine people born with extraordinary abilities—Mozart composing symphonies at five, Einstein reshaping physics with a simple thought experiment. Genius, in our collective imagination, is a mystical spark of brilliance, an exclusive gift of nature. But what if genius isn’t something you're born with? What if it’s something you can build? Richard Feynman, one of the most brilliant physicists of the 20th century, offers a different blueprint for genius: one that’s accessible to anyone willing to cultivate the right mindset and approaches to learning.

Feynman didn’t become a genius because of some supernatural endowment of intelligence. His genius was built through specific habits and attitudes—habits that anyone can adopt. What set Feynman apart wasn’t just his knowledge, but how he thought about problems, his relentless curiosity, and his fearlessness in the face of failure. These aren’t traits you’re born with; they are skills you can train, just like muscles.

Curiosity as the Foundation

Feynman’s journey began with a simple but profound idea: to understand something, you have to dive into it with unrelenting curiosity. Not the kind of curiosity that merely asks what something is called, but the kind that digs deeper, relentlessly asking why it works the way it does. As a child, Feynman’s father encouraged him to look beyond the surface of things. He would take young Richard on nature walks and point out not just the names of birds, but their behaviors, asking questions about why they acted as they did. This early training in looking deeper would become a hallmark of Feynman’s approach to everything.

“I learned very early the difference between knowing the name of something and knowing something,” Feynman said. This is a crucial distinction. Most people are content with the names and labels. They want the comfort of a tidy answer. But Feynman was never satisfied with superficial knowledge. He craved understanding. And that’s a habit anyone can develop. It’s about asking one more question when others stop. It’s about not being afraid to look foolish for not knowing because not knowing is just the first step toward understanding.

This type of curiosity isn’t passive. It’s not about sitting back and pondering; it’s active. It involves getting your hands dirty, experimenting, tinkering, and often failing. Feynman loved to play with radios as a kid, not because he wanted to become an engineer, but because he was fascinated by how they worked. He didn’t just want to hear music—he wanted to understand how the sound was transmitted. This hands-on curiosity, this compulsion to see things from the inside out, became a lifelong trait. It’s why, as a young man, he threw himself into fixing radios “by thinking,” as he put it, diagnosing problems by visualizing the circuits in his head.

Embracing Mistakes and Learning from Failure

Feynman’s second lesson is one of mindset. He didn’t view mistakes as failures but as opportunities to learn. In a world where everyone is trying to look smart, Feynman embraced the exact opposite approach. He was candid about his ignorance and saw each error as a path to deeper insight. As he famously said, “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool.”

Most people are terrified of making mistakes. They worry about what others will think, how they’ll be judged. But this fear of failure is a massive barrier to learning. Feynman’s approach was different: he turned mistakes into experiments, moments to test assumptions and refine his understanding. This mindset—seeing every error as a stepping stone—is something anyone can adopt, and it’s incredibly powerful.

Consider his experience at Los Alamos working on the Manhattan Project. Feynman was surrounded by the greatest minds of the time, each contributing to the most ambitious scientific endeavor in history. In such an environment, the pressure to perform flawlessly was immense. Yet, Feynman thrived not by knowing all the answers, but by persistently questioning everything—even when his questions made him look naive. He repeatedly broke through problems not because he was smarter than everyone else, but because he wasn’t afraid to be wrong. His courage to admit, “I don’t understand this; can we go over it again?” was what led to his most significant breakthroughs.

In one instance, Feynman was tasked with auditing the calculations related to the bomb’s energy release. Instead of accepting the methods already in place, he started from scratch, examining every detail for errors. It wasn’t because he distrusted his colleagues, but because he recognized that thorough understanding requires relentless scrutiny. It was this insistence on seeing the details and being willing to find and admit mistakes that ensured the project’s success.

Independent Learning and Unconventional Approaches

Feynman didn’t follow the beaten path. In school, he often pursued subjects that interested him personally rather than those deemed important by others. “I didn’t pay a lot of attention to what they told me was important. I always kept my own private list of what was worth learning,” he once said. This independence of thought is a key ingredient in building genius.

Too often, people conform to the prescribed ways of thinking. They follow the syllabus, read the recommended books, and stop there. Feynman’s genius came not from following instructions but from exploring the topics that intrigued him, often using unconventional methods. He famously developed his own approach to solving complex integrals—an approach he invented not because someone told him to, but because it was interesting to him. That’s the kind of learning that sticks.

In high school, he was given a calculus book and taught himself differential and integral calculus long before his peers. But it wasn’t just about learning advanced topics—it was about understanding them in his own way. Feynman’s independence wasn’t just about rebelling against traditional education; it was about finding joy and fulfillment in learning on his own terms. This is something anyone can do: carve out time to explore topics that fascinate you, not because they are on a test, but because they ignite a spark of curiosity. That’s the fuel for genius.

Feynman’s approach to independent learning was also reflected in his famous “Feynman Technique” for learning. He would choose a concept he wanted to understand deeply and try to explain it in the simplest terms possible, as if teaching it to a beginner. If he found gaps in his explanation, he would go back and fill those gaps, refining his understanding until the explanation was clear and simple. This method forces you to confront what you don’t know and encourages a deeper, more robust engagement with the material. It’s a technique that anyone, at any level, can use to build their own understanding.

Facing Challenges Without Fear

Another critical aspect of Feynman’s mindset was his fearless approach to challenges. He wasn’t intimidated by the reputations of others or by the complexity of the problems he faced. When Feynman was invited to work on the Manhattan Project, he didn’t balk at the enormity of the task or the prestige of the team. He simply saw it as another problem to solve.

“What I cannot create, I do not understand,” he once remarked. This was more than a philosophy—it was a challenge to himself to engage fully with every problem. It’s easy to back away from tough challenges, to let the fear of failure prevent you from even trying. But Feynman’s approach was to jump in, confident that even if he didn’t have all the answers, he would figure them out along the way.

This fearless approach was on display throughout his career, from his early work in quantum electrodynamics to his later, more public role in investigating the Challenger disaster. In each of these roles, Feynman didn’t see himself as an expert who already knew the answers. Instead, he saw himself as an investigator, someone willing to follow the evidence wherever it led, even if it meant challenging the conclusions of others. This mindset of courage and curiosity is not reserved for physicists or mathematicians. It’s a tool for anyone who wants to push beyond their limits and take on problems that seem insurmountable.

Practical Engagement – Turning Theory into Action

Feynman’s genius wasn’t confined to theoretical work. He deeply believed in the power of practical engagement, whether through teaching, hands-on experiments, or applying his knowledge to solve real-world problems. “If you can’t explain something in simple terms, you don’t understand it,” he said. For Feynman, the act of teaching was not just about helping others—it was a way to refine his own understanding.

Teaching forces clarity. It’s one thing to have a vague understanding of a concept, but it’s another to distill it so that someone else can grasp it. Feynman’s insistence on clear, simple explanations was a tool for his own learning, and it’s a practice that anyone can adopt. The more you engage with a concept—by teaching it, applying it, or even debating it—the deeper your understanding becomes.

Feynman’s approach to practical engagement is also reflected in his habit of challenging himself with hands-on projects outside of his professional work. Whether it was cracking safes at Los Alamos, learning to draw, or playing the bongo drums, Feynman believed in exploring and engaging with the world in a tangible way. He didn’t confine his curiosity to the realm of physics; he applied the same inquisitive mindset to all aspects of life. This breadth of engagement kept his mind sharp and his thinking fresh, illustrating that practical involvement, whether in work or hobbies, can be a powerful tool for intellectual growth.

Conclusion: The Blueprint to Building Genius

Richard Feynman’s life is a testament to the idea that genius is not a gift but a practice. It’s built on curiosity, resilience, independence, fearlessness, and engagement. These are habits and mindsets, not innate talents. They are skills that can be developed, refined, and strengthened over time.

The lesson from Feynman’s life is clear: if you want to build genius, start by training your mind. Be curious. Embrace mistakes. Follow your interests, not just the instructions. Face challenges head-on. And engage deeply with the world around you. Genius isn’t about what you’re born with—it’s about what you build.

In the end, Feynman’s approach is refreshingly democratic. It suggests that anyone, regardless of their starting point, can cultivate a powerful mind. It’s not about having all the answers from the start; it’s about asking the right questions and having the courage to pursue them. Genius isn’t a gift. It’s an ongoing project. And with the right tools and the right mindset, it’s a project that’s open to all of us.