Godless Country

Czechia’s crisis isn’t atheism—it’s apathy. But history shows renewal is possible. Change starts when people take responsibility, embrace ambition, and build the future.

1. The Atheist Capital of the World—And the Consequences of Believing in Nothing

Czechia is often called the most atheistic country in Europe. The churches are empty, the priests are gone, and God is, for most people, a relic of history. But the real problem isn’t just the absence of religion. It’s the absence of belief in anything at all.

Faith—whether in God, in progress, in national destiny—serves a purpose beyond theology. It gives people something to strive toward. It gives them a reason to act. When a society loses that, what replaces it is not reason or logic, but apathy.

Czechia is a perfect case study in what happens when a country doesn’t just abandon faith, but ambition itself. The defining attitude here isn’t rebellion, or even skepticism—it’s resignation. People don’t fight against bad systems; they endure them. They don’t dream of greatness; they settle for survival. No one expects things to improve, and so no one tries to improve them.

This manifests everywhere. In politics, the country is run not by visionaries but by managers—people who don’t build, but merely administer. In business, the most ambitious entrepreneurs leave, knowing that big ideas are more welcome elsewhere. In everyday life, people expect nothing from their leaders, nothing from themselves, and nothing from the future.

The result is stagnation—not just economic, but existential. The best and brightest don’t push forward; they keep their heads down. The talented don’t aspire to greatness; they joke about how pointless it all is. The whole culture operates on a kind of autopilot, where nothing gets better because no one believes that it could.

Other countries that abandoned religion filled the gap with something else. The French had their revolutionary ideals. The Americans had capitalism and self-reliance. The Soviets had communism, for better or worse. But Czechia abandoned faith and replaced it with nothing. And when a society believes in nothing, it has no reason to strive.

This is the crisis we face. Not economic decline. Not political corruption. Those are symptoms. The deeper sickness is that the country has lost any belief that effort is worth it. That change is possible. That the future can be better than the past.

And a country that loses that belief doesn’t just stagnate. It decays.

2. The First Step Out: Replacing Resignation with Responsibility

If this were just a Czech problem, it might seem like a local quirk—just another small nation going through a slow decline. But history shows that no country is doomed to stagnation forever. Cultures can shift. Mindsets can change. And it starts with one thing: a sense of responsibility.

Czechia’s current state isn’t just bad luck. It’s the result of choices—generational choices, cultural choices, personal choices. The idea that “nothing can change” is itself a choice. And the first step toward recovery is realizing that change is possible because it has happened before.

Look at Estonia. After the Soviet collapse, they could have fallen into the same passivity. Instead, they took responsibility for their future. They digitized their government, cut corruption, and built an economy that now outperforms much of Eastern Europe. The shift wasn’t just economic—it was mental. They stopped thinking of themselves as victims of history and started acting like architects of the future.

Or look at postwar Germany. Devastated, occupied, humiliated—yet within decades, it had rebuilt itself into one of the world’s strongest economies. How? By refusing to accept that past failures defined the future.

This is what Czechia must do. The culture of passive endurance must be replaced with one of active ownership—of problems, of solutions, of the country itself. Every country that has transformed itself did so because enough people stopped saying “that’s just how things are” and started saying “this is ours to fix.”

This shift doesn’t come from the government. It starts with individuals—people who refuse to be indifferent. A new generation that sees responsibility not as a burden, but as a source of power. A mindset that says: “If this country is broken, it’s because we let it be. And if it is to change, we are the ones who will change it.”

3. Reviving Ambition: How to Make Czechs Dream Again

The second step, after responsibility, is ambition. Taking ownership of the future is meaningless unless people actually want to build something better. And that’s the next challenge: reviving the idea that greatness is even possible.

Ambition isn’t just an individual trait—it’s a cultural one. Some countries reward it. Others suppress it. Czechia falls into the latter category. Here, the best way to be successful is to be quiet. Don’t aim too high. Don’t take too many risks. And whatever you do, don’t stand out.

This is learned behavior. It comes from history, from centuries of occupation where survival depended on not attracting too much attention. But other nations have broken out of this mindset. Take Poland. After 1989, they could have fallen into the same post-communist lethargy as Czechia. Instead, they embraced capitalism aggressively, attracted investment, and became one of Europe’s biggest economic success stories. They weren’t afraid to dream.

Or look at Israel. A tiny country surrounded by enemies, with no natural resources, yet now a global leader in technology and innovation. How? Because they built a culture where risk-taking is rewarded, not discouraged. They expect greatness from themselves. And so they achieve it.

Czechia needs this shift. It needs to celebrate those who take risks, who build, who dare to aim higher. It needs to stop treating ambition as arrogance and start seeing it as the key to the future. This doesn’t require government intervention. It requires a change in attitude—where success isn’t mocked, but admired.

The question every Czech should ask isn’t just “how do we fix what’s broken?” but “what can we build that has never existed before?” Because that’s how every great transformation begins—not by repairing the past, but by creating a future worth striving for.

4. Replacing Stagnation with Action: The Small Wins That Start Big Change

It’s easy to think that a culture of passivity is impossible to change. But history proves otherwise. The best way to break stagnation isn’t through a single, massive reform—it’s through small but meaningful victories that build momentum.

Look at Taiwan. In the 1980s, it was a country known for cheap manufacturing, not innovation. But instead of waiting for the government to act, young entrepreneurs, academics, and engineers started building a tech-driven economy from the ground up. They founded startups, established research labs, and created industries that barely existed before. Today, Taiwan is one of the world’s top technology hubs.

This is the lesson: big change doesn’t start with a national overhaul. It starts with small groups of people deciding to act. Czechia doesn’t need permission from politicians to become a country of builders. It needs individuals who refuse to wait.

Instead of complaining about bad institutions, create better alternatives—whether in business, media, or culture.

Instead of waiting for schools to modernize, build new educational platforms that actually prepare people for the future.

Instead of lamenting that all great startups happen elsewhere, fund and support ambitious entrepreneurs here.

Most revolutions don’t begin with a full-scale uprising. They begin when a few people start behaving as if the future is already different. And eventually, the rest of the country follows.

The key is to break the pattern of inertia—not by demanding that others change first, but by proving change is possible through direct action.

5. How to Replace Weak Leadership with Bold Leadership

One of the reasons stagnation persists in Czechia is that leadership is selected for caution, not competence. The system rewards those who play it safe, avoid conflict, and never take risks.

This is not unique to Czechia. Many countries have suffered from this problem—until they changed the way leadership works.

Look at Singapore in the 1960s. At the time, it was a poor, unstable, corrupt city-state. Its transformation came when meritocracy was enforced at all levels of leadership—not just in government, but in business, academia, and even civil society. Mediocre leaders were pushed out. Capable leaders were given power, regardless of their background. Today, Singapore is one of the most efficient and prosperous nations in the world.

Czechia needs to do the same: create a culture where leadership is earned, not inherited. This means:

Electing leaders who have a vision for the future, not just those who "manage" the present.

Breaking the cycle of political cynicism—supporting ambitious leaders, rather than assuming they’re all the same.

Promoting meritocracy in business and government—rewarding innovation, not just loyalty or seniority.

Most importantly, Czechs need to stop seeing leadership as something distant and corrupt and start seeing it as something they can influence. Strong leaders don’t emerge in a vacuum. They emerge when people demand something better.

6. The Power of Ownership: How to Build a Culture of Initiative

If there’s one cultural shift that could change Czechia more than any policy, it’s this: replacing the expectation of disappointment with a culture of personal ownership.

The biggest barrier to progress isn’t lack of talent or resources. It’s the widespread belief that “it’s not my job to fix things.” This mindset—ingrained over centuries of foreign rule and communist bureaucracy—has led to a culture where people complain, but few act.

Other nations have broken out of this trap.

Take Finland. After World War II, it was a small, vulnerable country caught between superpowers. It could have become a passive, dependent nation. Instead, it fostered a culture of ownership—where citizens took active roles in improving their communities, businesses innovated without waiting for government intervention, and education was shaped not just by officials but by teachers and parents. Today, Finland is one of the most dynamic and well-run societies in the world.

The shift from passivity to ownership doesn’t require waiting for the perfect moment. It starts when people change how they see their role in society.

A broken institution? Fix it, don’t just complain about it.

A dead-end job? Create something new, instead of staying in place.

A stagnant culture? Start movements, build businesses, fund artists—act as if the country is already changing.

The moment enough people take ownership, the culture shifts. Czechia’s history proves this: the Velvet Revolution didn’t happen because the government collapsed—it happened because people stopped waiting and started acting.

The same principle applies now. No permission is required. The shift begins the moment people decide that they are the ones who will build the future.

7. The Mechanics of Change: How Revolutions Succeed

One of the most dangerous myths in Czechia is that nothing ever changes. That history is something that happens to us, not something we shape. But history itself proves that’s not true.

Every great transformation—whether political, economic, or cultural—has followed a similar pattern:

A small, committed minority refuses to accept the status quo. The American Revolution didn’t start with a majority. Neither did the Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. or the Velvet Revolution in 1989. It began with a few people who decided that resignation was no longer an option.

They articulate a clear vision. The most successful movements don’t just fight against something—they fight for something. The Prague Spring wasn’t just anti-Soviet; it was pro-democracy. The best revolutions aren’t just about tearing things down—they’re about building something better.

They create momentum through visible wins. Revolutions rarely happen in one explosive moment. They build over time. The fall of communism in Eastern Europe didn’t start in 1989—it started years earlier, with small acts of defiance, underground movements, and cultural shifts.

The lesson? Change isn’t waiting for some grand uprising. It happens when enough people stop accepting mediocrity and start proving that better things are possible.

If Czechia is to break free from stagnation, it doesn’t need everyone to believe in a better future. It just needs enough people willing to act as if that future is already coming.

8. Why Hope is a Strategy, Not Just an Emotion

Hope is often misunderstood. It’s not wishful thinking. It’s not the belief that things will magically improve. It’s the decision that something is worth fighting for, regardless of the outcome.

Havel understood this better than anyone. He didn’t believe change was inevitable—he believed it was possible, and that possibility made it worth the struggle. This is what separates successful movements from failed ones. The ones that succeed aren’t necessarily the ones with the best conditions—they’re the ones that refuse to give up.

This is why hope is not just a feeling—it’s a strategy:

It sustains action when change seems slow. The Velvet Revolution didn’t happen overnight. It took years of small, unnoticed efforts before the moment of collapse arrived. If people had given up too early, history would have taken a different turn.

It creates a culture where action is normal. Once enough people believe that things can change, they behave differently. They start businesses instead of leaving. They demand more from leaders. They refuse to accept mediocrity in their institutions.

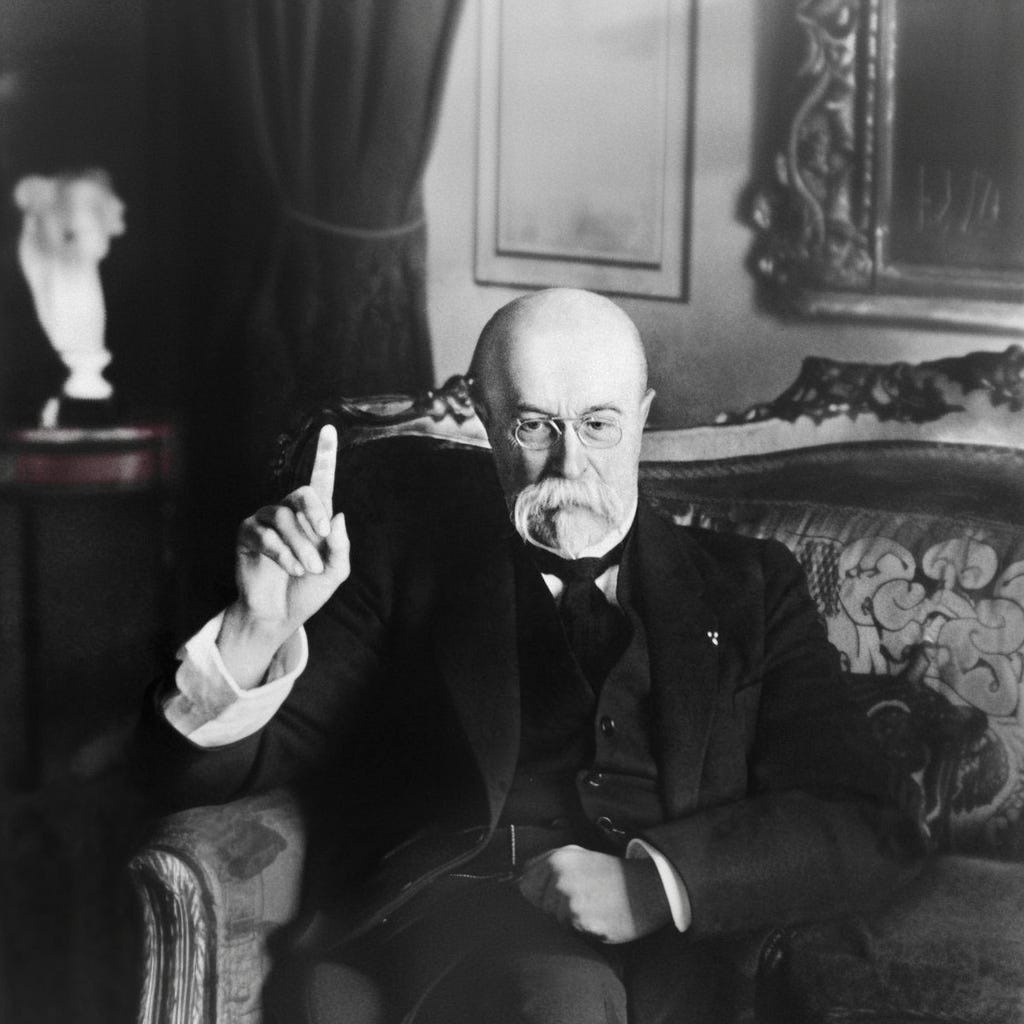

It makes leadership possible. No one follows cynicism. People follow those who believe in something. The reason figures like Masaryk and Havel succeeded was because they didn’t just describe problems—they inspired solutions.

Czechia has a choice. It can stay trapped in the belief that “this is just how things are.” Or it can choose the harder path—the one that says, even if success isn’t guaranteed, it is worth striving for.

That is what will separate those who merely survive from those who build something better.

9. Lighting the Fire: A Call to Action

So what now? What’s the first step?

The answer isn’t some grand government reform. It’s not waiting for the right leader to emerge. It’s not hoping that the world will change on its own. The answer is people choosing to act, even in small ways, right now.

Here’s how it starts:

Build, don’t just critique. It’s easy to complain about problems. It’s harder—but far more important—to create solutions. If the government is corrupt, build institutions that work around it. If the culture lacks ambition, create spaces where ambition thrives. Every successful movement in history started with people building the world they wanted, not just protesting the world they had.

Reward boldness, not caution. The problem with Czech leadership isn’t just the people at the top—it’s the culture that puts them there. If Czechia wants better leaders, it must stop punishing those who take risks. The countries that thrive are the ones where people celebrate innovation instead of mocking it.

Act as if the future is already better. The most powerful cultural shifts happen when people stop waiting for permission to change and start living as if the change is inevitable. This is how revolutions succeed—not because the majority wakes up one morning and decides to act, but because enough people start behaving as if a better world is already on its way.

This is how Czechia can break free from stagnation. Not with one dramatic moment, but with a steady, relentless push from those who refuse to believe that decline is the only option.

Because here’s the truth: the country has done this before. Masaryk built a nation from nothing. Havel led a revolution against all odds. Czechia’s greatest moments have always come when people believed in something bigger than themselves.

The only question is whether that spirit can be rekindled.

And the answer, as history shows, is yes.